It’s hard to believe the old man has been gone for twenty years today. Some memories are seared into my mind while others are fading into the sunset. Over the past year, I’ve been working on a book with his life lessons at the center but the process is much slower and it’s taking longer than expected.

Millrat: A Working Class Memoir About ALS, Adversity and the American Dream is Hillbilly Elegy meets Tuesday’s with Morrie. Over the past decade, the self-defeating victimhood narrative has become a moral virtue embedded in our schools and embraced by the media. Now, it has taken permanent root in American culture. In Millrat, I share my experience as a teenage caretaker of my Dad as he battled ALS for five years all while dealing with Mom’s bipolar disorder and eventual suicide. The purpose of the book is to show readers how faith, family, and community are essential to building the personal agency needed to handle rejection, overcome adversity, and learn from failure while in pursuit of the American Dream.

In the book, I show how I developed personal agency by absorbing the timeless wisdom and principles Dad practiced on a daily basis. In addition, he put me through testing, something that was required to pass into manhood. While such rituals have taken place around the world in their own form for thousands of years, I knew for certain that my childhood had elements that were far different than my peers. Technology and the breaking down the family unit has nearly wiped out this age old practice when it comes to training boys how to become men. Dad was not particularly religious and his education was minimal so it posed the question: Where did his values come from and why was he trying to pass them on to me? The simple answer is that we tend to follow what our parents did, or we cherrypick the parts that we think are important and discard the rest.

Family History

To better understand these values, I needed to research family history. A very abridged version: Ordways go as far back as Robert, born in 1460 in Bengeworth, Worcestershire, England. James immigrated to Newbury, Essex, Massachusetts Bay Colony, British Colonial America in 1648. Ninety years later, John moved the family to New Hampshire. Daniel moved to Crittenden County, Kentucky, by 1840, according to the census, and the county was officially established by the state two years later. Mineral mining began in 1835, but fluorspar did not expand until the 1890s with the design of the open-hearth steel furnace, where fluorspar was used as a flux. Production was good for WW1, WW2, and the Korean War but sporadic in between, with imports starting to threaten the industry in the 1930s. The population of Crittenden peaked in 1900 at 15,000 and has been in slow decline since. Ordways have a long history of loving the rural life, however, zero upward economic mobility was acquired during those several hundred years.

Southern Migrants, Northern Exiles

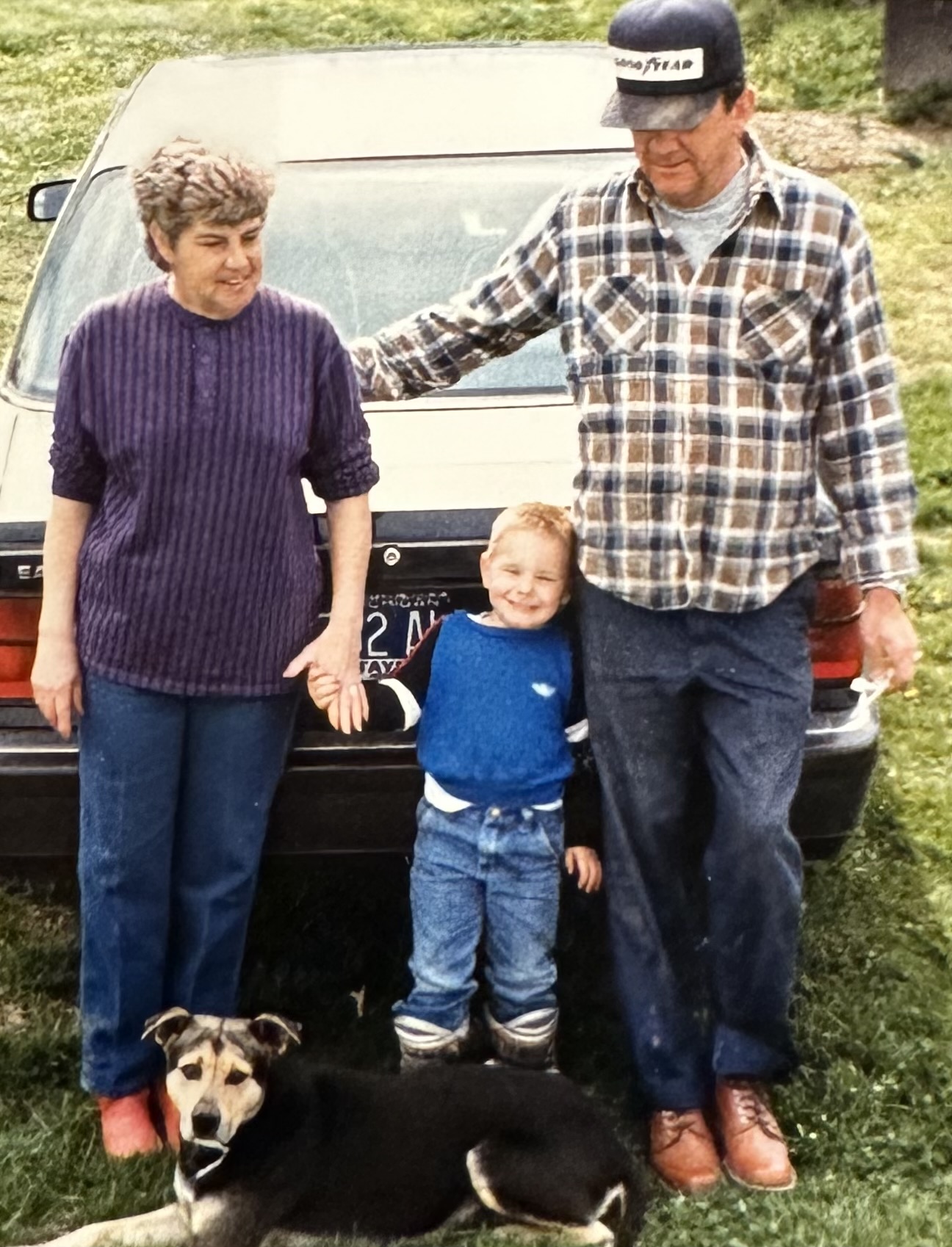

After 100 years in rural Kentucky, Papaw and Mamaw Ordway were the tail end of the family name and joined the Great White Migration (1945-60), which was one of the largest internal migrations in the history of the United States. Foreign competition and trade policy depressed the mineral mines in Western Kentucky all while manufacturing was booming up north so my grandparents headed to Gary, Indiana for economic opportunity in the late ‘50s. They were some of the last arrivals, after the Great Black Migration and decades after both Eastern Europeans and Mexicans put down permanent roots in The Region.

While Kentucky had one of the largest out-migration totals in the twentieth century, data shows that more flatlanders from the western part of the state headed north than their counterparts from Appalachia. Kentuckians practiced chain migration as industry loved hiring family, which provided continuity and stability for both. Many had multiple families under one roof while others were looking for jobs. Most notable is that such migrants were known to be very frugal in all aspects of life. I can attest that it carried through to my childhood.

Honor: adherence to what is right or a conventional standard of conduct.

The unifying theme I see in southern migration is the notion of Honor, which is about one’s external character as it relates to family standing within the community. In addition, there is a fierce loyalty to faith, family, and community… although sometimes church went by the wayside with the demands of work life in the mill. That loyalty led to divided hearts, wanting to stay in the South with family but needing and ultimately depending on opportunities in the North. After being gainfully employed, Kentuckians went home often, but men polled at a much higher rate than women when it came to homesickness, and many struggled to adapt to an agrarian lifestyle with open land as they were suddenly cooped up in tiny apartments with family when not putting in long shifts at the mill. Upon Papaw’s retirement from U.S. Steel, he moved back to Kentucky with Mamaw in the late ‘80s, but most of her family would stay up north indefinitely.

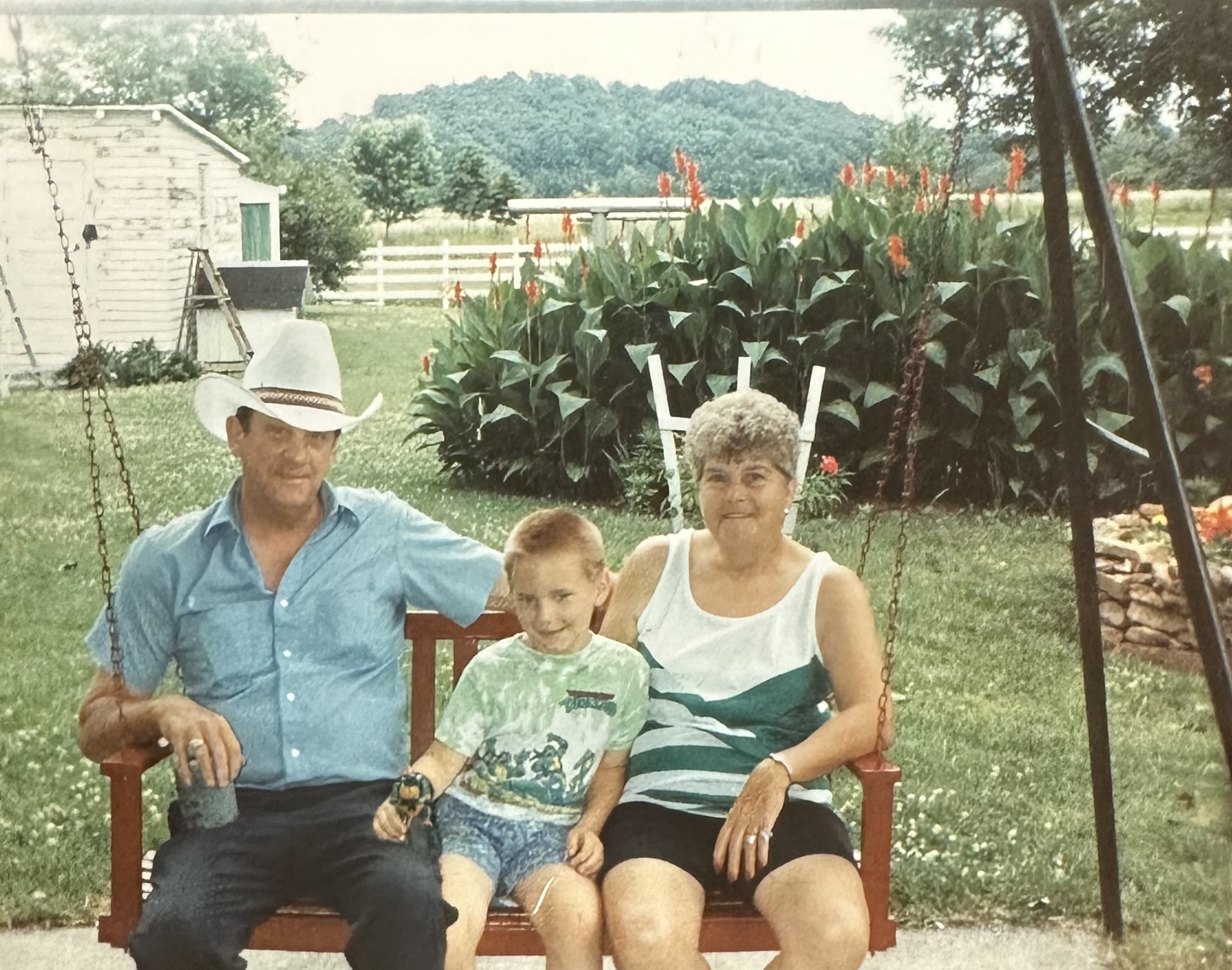

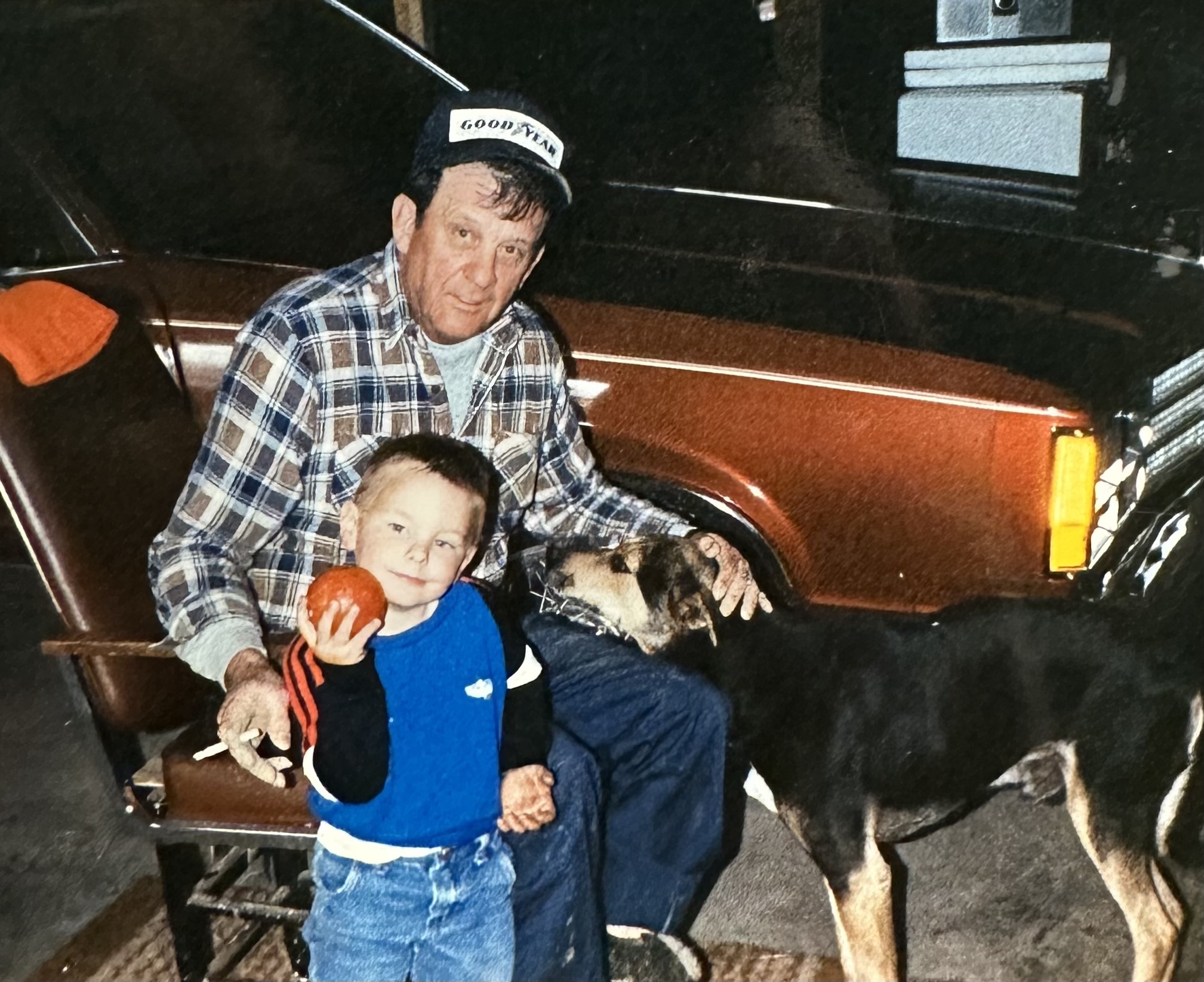

Dad’s upbringing would be a repeat of his fathers: with honor, strong work ethic, brutal honesty, ‘quiet and carry a big stick’ mentality, southern sayings, and an undying love of Kentucky, including his hunting property in Sheridan and the Kentucky Wildcats. There are many sayings that Dad had, and some were borrowed from my grandparents as I lived with them in Kentucky from when I was 3-4 (88-89) and spent every summer there until I was 12. Some were easy to remember because ‘storytelling’ down south had a lot of repetition. After all, our main hobby was sitting on a swing on a porch or in the backyard.

If the principle or value was important, Dad didn’t have a problem repeating himself when the time arose. The more he said it, the easier I remember it. Sometimes, he explained them, and other times, it felt like a parable for me to figure out on my own. Either way, I’m trying to work his quotes into my book without having to ’spell everything out’ and take the reader away from the main themes.

“All a man has is his word.”

This is Southern Honor at its finest. You only get one reputation, and the family name must have good standing in the community. In rural societies, reputation is about power and survival. To be seen as weak means you get run over. Also, if you get black-balled, you are on your own. That’s bad in a community where trading, borrowing, and helping each other is the centerpiece. A gentleman’s handshake and commitment were the highest level of integrity for Dad, and he expected me to conduct myself as such.

“You need skin in the game.”

Dad was big on making sure I had ownership in whatever risks I took. If I wanted a particular ‘toy’ or possession, for instance, he said he would meet me halfway financially. This was to demonstrate to him my ability to save and to have ownership in the process. He also said rich kids would be worse off when their parents outright bought them fancy things because there was no reason to respect their own possessions when mom and Dad would just buy them new ones. Dad was big on personal responsibility, and I mean BIG on it.

“I’m your father, not your friend.”

Dad understood that his job was to help me become self-sufficient. In addition, he let me know that his role was clearly defined. He rendered unconditional love and support and something called ‘reality discipline.’ He was critical of me in public and praised me in private. As my coach in Baseball All-Stars in 5th grade, he was the anti-nepotist, making me run more and bat less as if I needed to be singled out in the worst way. He enjoyed telling me on multiple occasions that life is not fair.

Most parents today are looking for validation, acceptance, and, ultimately, a friendship with their children as a means to fill a void in their own past. This parent also tends to live vicariously through their kids by trying to force (not nudge) them toward their own preferences in academics, sports, choice of career, or, in the worst of cases, spouse. I see ‘helicopter parenting’ as a massive overcorrection by people who grew up with absentee parents. This spans all current generations, is out of control, and contributes to the lack of leadership in churches, government/politics, business, and the like.

“Don’t worry about what other people are doing.”

A lot of my friends didn’t have chores, they received allowances, they were able to stay out late, and the list goes on. He would have none of this. He was very adamant that I kept my head down and focused on what was before me, whether that be in school, sports, or whatever. You see this today in the public sphere (esp social media) where folks are too worried about everyone else before ensuring their own house is in order. Dad thought we each had enough flaws and that time was best spent on our own self-improvement. He abhorred gossip of any kind and thought we should be listening far more than talking.

“Always leave nature better than you found it.”

Dad was a hardcore conservationist, a Teddy Roosevelt of sorts. Sometimes I think he respected the woods more than people. That was his get away and while hunting, he could sit out there for hours, perhaps days, never see a deer and be perfectly content. Between hunting, fishing and camping, he was adamant that we leave no trace. There are two types of people in this life: those that pick up their trash and those that dont.

“Treat every gun as if it were loaded. Always check it. Never point it at anyone.”

This saying is not unique to him in any way, but I shot my first gun when I was about 8. It was in the middle of a field in Culver, Indiana and about an hour away from home. The gun was a 20 gauge single-shot shotgun, and I cried, mostly because I was scared and just didn’t want to shoot the gun. Afterward, I fell in love, but Dad always made sure I developed a deep respect for guns and the seriousness that surrounds them. Dad took gun safety to another level, and he had zero tolerance for it. If you respect your gun, it will respect you. It’s the Second Amendment for a reason. Without personal honor and personal responsibility, the right might be in the constitution but is in jeopardy… because of folks who do not have honor.

“Someone always has it worse than you. No thumb sucking. No whining.”

Dad just really didn’t tolerate complaining about the menial things. He had a very narrow scope of what ‘real suffering’ was but he was always helpful at walking me through or explaining my failures in a way that reformed them as teaching moments. Did I mention he said life is unfair?

“You get what you pay for.”

We didn’t have a lot of nice things, but Dad understood what value meant. Maybe it was the union man in him but he made a real effort to buy as much Made in America as he possibly could. He was big into needs vs wants and putting one’s money where it made the most sense… at least to him. For instance, he used to wear this flag t-shirt that said “try burning this one”. The shirt had all kinds of holes as he wore it into the ground, and I was embarrassed to be seen with him in public when he wore it. At the same time, he went out of his way to buy US-made Craftsman tools for the garage. They were expensive, but he said they were guaranteed for life, so the price was worth it.

“Treat other people’s stuff better than your own.”

For folks that don’t grow up with money, there is a lot of trading and borrowing that happens, not to mention trips to pawn shops and yard sales. Yard tools, hunting/fishing equipment etc. For the frugal, having loyal friends is a way to ‘expand your possessions’ without have actually to own anything. I think this is tied back to honor and personal reputation. If you destroy someone else’s stuff and give it back to them, odds are that will reflect poorly on your character, and the opportunity to borrow again is unlikely.

“Figure… it… out.”

When you don’t have money, you can’t just call up the plumber, the HVAC, or the roofer. While chores were a given, weekends were often filled with projects and other yard-related exercises that I never signed up for. Dad didn’t like giving me easy answers to anything, as that was part of the learning experience. This also offered a safe space for me to fail. ‘Figure it out’ was an expression I disliked but grew to accept, respect, and enjoy as I got older and became curious about mechanical things like car engines.

“If you’re going to do something once, do it right. Measure twice, cut once.”

Dad really tried to reinforce ‘street smarts’ over academics on a regular basis. He knew the most optimal way to mow the lawn, skin a deer, clean gutters, practically any outside blue collar activity. He would let me figure this out on my own and if I didn’t, explain a better way to do something that took less, time, energy and in some cases, money.

“If you want something done right, you have to do it yourself.”

Sometimes, I think this is personal pride over opportunity cost. Other times, I think this is him being upset at me for not doing things the way he would have done it. There is a level of ownership and agency that comes about when you fix your own car, repair the roof, and the like. I liken this to an Eastern European scrapper mentality. It’s really good in your early days, but an entrepreneur would say this kind of pride is not scalable. If you start making money, it’s best you outsource things so you can channel your efforts toward other things.

“Never trust friends of friends.”

In the lower end of the working class, people steal, especially hillbillies. They will study you like no other. I remember when I was 6 or 7, someone broke into our shed and stole all of Dad’s fishing and hunting equipment. It was one of the few times in my life I saw him cry. We spent a lot of time together in the garage, but after he got sick, it was usually me and a few of my friends. One time, a friend came over and brought a friend whom I did not know. Dad was pretty upset about it. We had some decent possessions in the garage, mostly tools and such. He said I had no idea if that third party was eyeballing something or planning a way to break in. One thing about Southern Honor is it is fundamentally exclusionary. You are part of the in-club or not. Trust is a deep component of that.

“Don’t half-ass it. No loafing. Give it 110%. Leave it all on the field.”

As much as I would like to say Dad was all about results, what he really cared about was effort and the learning process that came along with it. While parents today are playing politics to make sure their kid is getting more playing time (even when it’s unwarranted), Dad had no problem coaching me from the stands. When I did league basketball in 6th grade, he was the only parent to show up to practice from 5-7 p.m., sit on the opposite bench, and let me know when I wasn’t performing. During All-Stars, he said I wasn’t ready for the ‘big leagues’ as an 11-year-old, and I ‘rode the pine’ for those few games with no time in the field and batting once.

“Good grades aren’t everything, you need seat time (experience). You learn by doing.”

Dad and I had most of the same teachers in high school yet he was a C-D student and I was an A-B student with a full ride to any university in the state of Indiana. Dad still demanding high grades but he also understood that there is a difference between theory and practice. He knew that I was book-smart but always pushed me to use my hands for problem-solving.

“Do I have to put my foot in your ass? Do I need to put a knot on your head? Do I need to draw you a picture?”

Rhetorical questions were a southern man’s version of ‘bless your precious heart’ from Mamaw. It provided a moment to reassess, become alert and pay attention… or perhaps a moment to “get your head out of your ass”. Pretty sure these questions were about reinforcing the use of common sense.

“If you ever smoke (a cigarette), I’ll kick your ass. Do as I say, not as a do.”

Let’s add ‘put on your seatbelt’ to this hypocrisy as well. Dad was keenly aware of his own shortcomings, bad habits, and perhaps addictions, but he wanted to prevent those things from being generational. Even though there were patterns of contradiction in his behavior, words alone were enough to keep me on the straight and narrow. Both his smoking and seatbelt comments came when we were driving to Culver to hunt on the weekend. Twenty years later, and I’ve never smoked a cigarette for fear he’ll come out of the ground for me.

“No house humping.”

This is an extension from Mamaw from when I lived in Kentucky. When the weather was nice out, I was expected to spend my days outdoors. This was somewhat easy to practice as we didn’t get air conditioning added to our house until after my Dad was already diagnosed with ALS in 98. I’m not sure if he thought AC was domesticating or made men weak but it was certainly a way to keep me from getting addicted to video games. I also recall saying “I’m bored” was a high offense. Dad said, “Oh, you’re bored, I’ll give you something to do.” Seems like his list of projects was endless; there was no need to give him ammo to put me to work more.

“Don’t give me no lip. No back talk.”

Respect is everything. A child’s respect for their parent…even more. ‘Mouthing off’ had consequences. I probably addressed my Dad more by the title of ‘sir’ than anything else. Strict adherence to hierarchy is Southern Honor. The best attribute a parent can have is the ability to tell their children ‘no’ regularly. It sets the stage for expectations, especially between needs and wants.

“Never watch another man work. Don’t stand around with your hands in your pockets.”

Being useful was really important to Dad. Being helpful to others even more so. If he was doing some sort of complicated task, I would get yelled at for standing around and watching. Instead, he wanted me to ask him how to be useful. That’s where the teaching moment began.